Imagining the past

Faces in the Water

These old people sit at the special table, have cream on their pudding, and are hurried early to their rooms, undressed, put to bed and locked in. Immediately the nurse is gone they get out of bed and potter around the room making sure looking for things seeing to things. They continue thus, restlessly, most of the night and in the morning after only fitful sleep, sometimes with their beds wet and dirty, they begin again to solve the puzzle of being where they are, of not being allowed to go outside, of losing their garters and their handkerchiefs and of being involved in the complexities of going from one place to another, of going to the lavatory and remembering to wipe themselves, of being led from dayroom to meal table and back again.

The old women will eventually be put to bed for the last time; they will lie in the dreary sunless rooms that stink of urine; they will washed and "turned" daily, and the film, the final deception, will grow over their eyes. And one morning, if you walk down the corridor through Ward One, you will see in the small room where one of the old women has been sleeping, the floor newly scrubbed smelling of disinfectant, the bed stripped, the mattress turned back to air; the vacancy created in the night by death.

Better not to

Dunedin Railway Station

Methods of treatment had made great advances

Maggie

An interview with a doctor had been arranged. He explained that if Mum had taken ill in this age things would have been different. Much better understanding and methods of treatment had made great advances. I was very sad thinking of what might have been.

From then on we visited occasionally. After these hospital visits I felt very upset. The doctor said we had to weigh up the possible good it was doing Mum and the harm it was doing me. The seemingly wasted years preyed on my mind to a certain degree.

I was never ashamed of my mother because of her condition, but felt unable to speak to her, except to close friends. Mental illness had a terrible stigma attached to it. Having a mother at Seacliff would be a disgrace in the eyes of so many folk. Only MAD people lived there. Not being able to talk freely about your mother or father was a drawback. I felt “out of it” and a bit of an outcast, in that area. My gentle, sweet, kind, artistic mother was categorised.

Inmates of Seacliff

Faces in the Water, Janet Frame, p.58

Maggie

We arrived at the hospital. It was a large, dismal stone building, like a medieval castle, with small windows. After being admitted to the waiting room we anticipated our meeting with my mother. I was trembling inside and apprehensive. Bun was supportive and loving. A hushed stillness, austerity and the sound of keys unlocking and locking doors, was my first impression. When I saw this little lady being brought towards me I KNEW instinctively that she was my mother. She looked like an older version of my sister Rae. All sorts of emotions surged through my heart and mind. I had not seen her since I was a little girl. It was an overwhelming experience. The mother I always longed for, the mother I had cried on my bed at night time for many years when I was young was standing before me. The feeling was indescribable.

Bun and I introduced ourselves. We all sat down in comfort to talk. Mum said she had believed I was dead, killed in the accident I had at Mosgiel Junction with Uncle Jack. She remarked that good health was hard to get. By her general conversation it seemed her mind was still in a past era. We did not stay long. I found the visit a great emotional strain.

Jack

Marshall approached a member of AA to enquire how we could help our father overcome his drinking problem. Mr. Fraser, father of my friend Elsie, who was a ‘dry’ alcoholic went to talk with dad. Dad agreed to try out the plan of recovery.

This took a tremendous amount of willpower. My sister Rae rang me often to report progress. Dad was making a stupendous effort but the toll was devastating. He would arrive home from work, having bypassed the hotel, absolutely pouring with perspiration and trembling. This went on for some considerable time. The taunts and persuasive remarks from his workmates finally broke his resolve. He reverted to his old habits much to our disappointment.

When Bun wanted to ask my father for my hand in marriage I was rather nervous. Introductions went well. Dad was affable and pleasant. Bun, in his soft voice, told Dad he wished to marry me and would Dad give his permission. Dad’s response was, “If Isobel is happy, then it’s alright with me”.

Madness and Civilization

Throughout Madness and Civilization, Foucault insists that madness is not a natural, unchanging thing, but rather depends on the society in which it exists. Various cultural, intellectual and economic structures determine how madness is known and experienced within a given society. In this way, society constructs its experience of madness. The history of madness cannot be an account of changing attitudes to a particular disease or state of being that remains constant. Madness in the Renaissance was an experience that was integrated into the rest of the world, whereas by the nineteenth century it had become known as a moral and mental disease. In a sense, they are two very different types of madness. Ultimately, Foucault sees madness as being located in a certain cultural "space" within society; the shape of this space, and its effects on the madman, depend on society itself.

His central argument [about madness and art], however, rests on the idea that modern medicine and psychiatry fail to listen to the voice of the mad, or to unreason. According to Foucault, neither medicine nor psychoanalysis offers a chance of understanding unreason. To do this, we need to look to the work of "mad" authors such as Nietzsche, Nerval and Artaud. Unreason exists below the surface of modern society, only occasionally breaking through in such works. But within works of art inspired by madness, complex processes operate. Madness is linked to creativity, but yet destroys the work of art. The work of art can reveal the presence of unreason, but yet unreason is the end of the work of art. This idea partly derives from Foucault's love of contradiction, but he feels that it reveals much about modern creativity.

Get well soon

From 1919 until his death in 1950 Nijinsky was either in mental institutions, in hospitals or an invalid. Nijinsky wrote in 1919:

I want to weep but I cannot because my soul hurts so much that I fear for myself. I feel pain. I am sick in my soul but not in my brain. The doctor does not understand my sickness. I know what I need in order to be well. My sickness is too great for me to be cured soon. I am not incurable. I am sick in my soul. I am poor. I am a beggar. I'm unhappy. I'm hideous.

Doctors have the annoying every-recharging faith of Christians. Regardless of the catastrophic failure of Christian feeling or reason to stop evil or insanity they fountain of hope springs eternal. Our biographer of the penis says:

I can think we can do more to help someone like Nijinsky today than was possible when he became so disturbed.... Much better medication can now be prescribed for the control of disabling anxiety, fear and depression. Cylic mood disorders can be regulated. Confusion, rage, mania, hallucinations, and disabling mental states can be managed more effectively. Interpersonal techniques, psychotherapy, and marriage counselling have become more sophisticated. "Catatonia" has almost disappeared, and the incidence of "schizophrenia" is declining. Genetic, environmental, and social sources of mental disturbance are now better understood. Special programmes for the rehabilitation of dancers and other performing artists are available in many major cities. Long-term hospitalisation of psychiatric patients is almost unheard of nowadays. (p.342)

Maggie

Dance - Part Seven

Dunedin Railway Station was finished in 1906. It's remarkable on the outside, but the main foyer where you buy your tickets is incredibly elaborate. The amount of detail that they put into the ticket booths, and staircases and doorways is really impressive. I suppose that railway stations back then were real status symbols, like international airports now.

Dunedin Railway Station was finished in 1906. It's remarkable on the outside, but the main foyer where you buy your tickets is incredibly elaborate. The amount of detail that they put into the ticket booths, and staircases and doorways is really impressive. I suppose that railway stations back then were real status symbols, like international airports now.Dunedin City Council tells us that the DK Travel Guide series lists this railway station as one of the top 200 places to see in the world. This puts it in the same category as the Taj Mahal. I don't want to disparage the judgement of travel guide writers, but I feel someone working their way through the list might be a bit underwhelmed when the arrived outside the entrance of the Dunedin Railway Station.

Nevertheless, Dunedin is a city filled with remarkable buildings.

Once upon a time a great deal of money used to buy a city flash architecture. Dunedin was built on the gold rushes of the 1860s. In the second half of the 19th century it was New-Zealand's premiere city.One man responsible for the look of Dunedin, Oamaru, and other places in the region was architect Robert Lawson. He designed First Church, Larnach Castle and Otago Boys' High School amongst other structures.

Unfortunately he came a cropper with his design of Seacliff Lunatic Asylum. Even before it has been finished there were land slips that rendered sections of the structure unsafe.After a glittering career Robert Lawson was forced to flee to Australia (how awful).According to Michael King there were darker reasons that Seacliff was doomed:"[Otago Maori] believed that the authorities had courted physical and psychic disaster by building the hospital over a tribal burial ground. According to this interpretation, the structural collapses, the fire, and the general air of terror said to prevail in the wards holding the most disturbed patients were all consequences of a failure to respect the ethos and the tapu of the location."

Unfortunately he came a cropper with his design of Seacliff Lunatic Asylum. Even before it has been finished there were land slips that rendered sections of the structure unsafe.After a glittering career Robert Lawson was forced to flee to Australia (how awful).According to Michael King there were darker reasons that Seacliff was doomed:"[Otago Maori] believed that the authorities had courted physical and psychic disaster by building the hospital over a tribal burial ground. According to this interpretation, the structural collapses, the fire, and the general air of terror said to prevail in the wards holding the most disturbed patients were all consequences of a failure to respect the ethos and the tapu of the location."Wrestling with the Angel, Michael King (p.73)

*

It's cold. The platform at Dunedin Railway Station is very long. My mother is waiting. Marshall often runs late, but this time he is very late. Perhaps he gets off a train or, this is better, perhaps my mother is waiting at the front of the station and he comes across the car park and garden.

It's getting late. You can smell the smoke of the fireplaces in Dunedin; it's an earthy smell. He apologises for being late, hesitates, and then tells her about his mother. There is the din of a train coming into the station. All those men in suits in hats heading home after work.

It's a nice image, but remember, it's not true.

When Mum was dying Marshall met her for the first time in his memory. I thought he was very brave to visit her, but he wanted to. She gave him such a piercing look. Our Uncle Charlie, who was with us said, “She must think you are Jack, your father”. Charlie thought Marshall resembled Dad in his younger days.

My mother says that when Marshall came back he was a little shell-shocked: "an old woman with no teeth," he said. He had never met her before in his memory. Perhaps if he wanted a flattering image of his mother he shouldn't have gone at all.

My mother says that when Marshall came back he was a little shell-shocked: "an old woman with no teeth," he said. He had never met her before in his memory. Perhaps if he wanted a flattering image of his mother he shouldn't have gone at all.These old people sit at the special table, have cream on their pudding, and are hurried early to their rooms, undressed, put to bed and locked in. Immediately the nurse is gone they get out of bed and potter around the room making sure looking for things seeing to things. They continue thus, restlessly, most of the night and in the morning after only fitful sleep, sometimes with their beds wet and dirty, they begin again to solve the puzzle of being where they are, of not being allowed to go outside, of losing their garters and their handkerchiefs and of being involved in the complexities of going from one place to another, of going to the lavatory and remembering to wipe themselves, of being led from dayroom to meal table and back again.The old women will eventually be put to bed for the last time; they will lie in the dreary sunless rooms that stink of urine; they will washed and "turned" daily, and the film, the final deception, will grow over their eyes. And one morning, if you walk down the corridor through Ward One, you will see in the small room where one of the old women has been sleeping, the floor newly scrubbed smelling of disinfectant, the bed stripped, the mattress turned back to air; the vacancy created in the night by death.

Faces in the Water, Janet Frame, pp.60-1

Maggie died in 1959.

Nijinsky died in 1950. Out of the past we invent stories. Mr. Ostwald made up this story about thirty years of unhappiness. It might not be true, but it is a nice story.

"Nijinsky looms as a magnificent example of a man who achieved greatness and suffered miserably. Self-sacrificing, creative, destructive, and victimized by misfortune, he inspired an entire generation of dancers, not to mention the musicians, painters, designers, sculptors, writers, poets, and psychiatrists whose lives he profoundly affected. Movement was his metier. It freed him from the confines of a small environment in St. Petersburg, and propelled him into the heady world of the Ballets Russes. He danced his way around globe, and he leapt into that mysterious universe called madness. He was a saint, a genius, a martyr, and a madman. One can see him still, arcing in space, jumping and flapping, cavorting and flailing, shooting into the sky, suspended, laughing, crying, grimacing, screaming. He remains a myth, an apparition, an emblem, a creature of fantasy, a biological creation, a fleeting image of God. Nijinsky, the God of the Dance. (pp.342-3)

"Nijinsky looms as a magnificent example of a man who achieved greatness and suffered miserably. Self-sacrificing, creative, destructive, and victimized by misfortune, he inspired an entire generation of dancers, not to mention the musicians, painters, designers, sculptors, writers, poets, and psychiatrists whose lives he profoundly affected. Movement was his metier. It freed him from the confines of a small environment in St. Petersburg, and propelled him into the heady world of the Ballets Russes. He danced his way around globe, and he leapt into that mysterious universe called madness. He was a saint, a genius, a martyr, and a madman. One can see him still, arcing in space, jumping and flapping, cavorting and flailing, shooting into the sky, suspended, laughing, crying, grimacing, screaming. He remains a myth, an apparition, an emblem, a creature of fantasy, a biological creation, a fleeting image of God. Nijinsky, the God of the Dance. (pp.342-3) Dance - Part Six

It was not until I met Bun and we were “going together” that I started to visit Mum. Bun was amazed that I did not visit her. He immediately made arrangements for a visit. Naturally I was a little fearful. I had no idea what to expect.We arrived at the hospital. It was a large, dismal stone building, like a medieval castle, with small windows. After being admitted to the waiting room we anticipated our meeting with my mother. I was trembling inside and apprehensive. Bun was supportive and loving. A hushed stillness, austerity and the sound of keys unlocking and locking doors, was my first impression.

It was not until I met Bun and we were “going together” that I started to visit Mum. Bun was amazed that I did not visit her. He immediately made arrangements for a visit. Naturally I was a little fearful. I had no idea what to expect.We arrived at the hospital. It was a large, dismal stone building, like a medieval castle, with small windows. After being admitted to the waiting room we anticipated our meeting with my mother. I was trembling inside and apprehensive. Bun was supportive and loving. A hushed stillness, austerity and the sound of keys unlocking and locking doors, was my first impression.  When I saw this little lady being brought towards me I KNEW instinctively that she was my mother. She looked like an older version of my sister Rae. All sorts of emotions surged through my heart and mind. I had not seen her since I was a little girl. It was an overwhelming experience. The mother I always longed for, the mother I had cried on my bed at night time for many years when I was young was standing before me. The feeling was indescribable.Bun and I introduced ourselves. We all sat down in comfort to talk. Mum said she had believed I was dead, killed in the accident I had at Mosgiel Junction with Uncle Jack. She remarked that good health was hard to get. By her general conversation it seemed her mind was still in a past era. We did not stay long. I found the visit a great emotional strain.

When I saw this little lady being brought towards me I KNEW instinctively that she was my mother. She looked like an older version of my sister Rae. All sorts of emotions surged through my heart and mind. I had not seen her since I was a little girl. It was an overwhelming experience. The mother I always longed for, the mother I had cried on my bed at night time for many years when I was young was standing before me. The feeling was indescribable.Bun and I introduced ourselves. We all sat down in comfort to talk. Mum said she had believed I was dead, killed in the accident I had at Mosgiel Junction with Uncle Jack. She remarked that good health was hard to get. By her general conversation it seemed her mind was still in a past era. We did not stay long. I found the visit a great emotional strain.Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

In the early days I looked with pity and curiosity and wonder upon the few patients in the observation ward who would be there “forever” – Mrs. Pilling, Mrs. Everett who, as an inexperienced overwrought young mother, had murdered her little girl; Miss Dennis, slight, sharp tongued, with neatly rolled grey hair, whose days were devoted to “doing out” the Charge Room at the Nurses’ Home, polishing the silver and the water glasses and the fruit dishes of the illustrious white-veiled sisters; and the few other permanent patients who comprised those who knew the rules and could explain them – how when you were well enough you were given limited parole.

An interview with a doctor had been arranged. He explained that if Mum had taken ill in this age things would have been different. Much better understanding and methods of treatment had made great advances. I was very sad thinking of what might have been.From then on we visited occasionally. After these hospital visits I felt very upset. The doctor said we had to weigh up the possible good it was doing Mum and the harm it was doing me. The seemingly wasted years preyed on my mind to a certain degree.I was never ashamed of my mother because of her condition, but felt unable to speak to her, except to close friends. Mental illness had a terrible stigma attached to it. Having a mother at Seacliff would be a disgrace in the eyes of so many folk. Only MAD people lived there. Not being able to talk freely about your mother or father was a drawback. I felt “out of it” and a bit of an outcast, in that area. My gentle, sweet, kind, artistic mother was categorised.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

Janet Frame having failed to maintain a good level of response to the ordinary physical methods of treatment... is deemed to be a suitable subject for Prefrontal Leucotomy Operation to which I hereby give my consent... I understand to what extent this operation may offer a measure of relief and the minor element of risk involved."

Janet Frame's friend was also at Seacliff and had a leucotomy. Afterwards:

"[They] were talked to, taken for walks, prettied with make-up and floral scarves covering their shaved heads. They were silent, docile; their eyes were large and dark and their faces pale, with damp skin. They were being 'retrained' to 'fit in' to the everyday world, always described as 'outside'. In the whirlwind of work and shortage of staff and the too-slow process of retraining, the leucotomies one by one became the casualties of withdrawn attention and interest."

Dance - Part Five

In 1998 I had just finished my M.A.

In 1998 I had just finished my M.A.This book first arose out of a passage in Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought - our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography - breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten our age old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes "a certain Chinese encyclopaedia" in which it is written that "animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies." In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap... is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own [system of thought], the impossibility of thinking that.

The Order of Things, Foucault, p.xv

Foucault was very big on categories, on how they appear natural to us but are actually fairly arbitrary intellectual systems that have changed radically throughout history.

His first two books were about the definition of madness and the development of the mental institution.

*

Some time after the birth of Marshall my mother became mentally ill. She was admitted to Seacliff Hospital. Apparently, she spent a few weeks there and was allowed home with strict instructions that she was to be taken care of. Dad’s sister, Auntie Jessie, came down from Timaru to stay with her husband Doug in tow. From all accounts Auntie Jessie was pregnant at the time and had a miscarriage so Mum ended up looking after her. Mum had a relapse and was returned to hospital and lived there for the rest of her life.

Some time after the birth of Marshall my mother became mentally ill. She was admitted to Seacliff Hospital. Apparently, she spent a few weeks there and was allowed home with strict instructions that she was to be taken care of. Dad’s sister, Auntie Jessie, came down from Timaru to stay with her husband Doug in tow. From all accounts Auntie Jessie was pregnant at the time and had a miscarriage so Mum ended up looking after her. Mum had a relapse and was returned to hospital and lived there for the rest of her life.Dad could have divorced my mother as she was a resident at Seacliff Hospital for many years, but he chose not to. I was struck by the fact that he regularly watered and cared for her asparagus fern on the front veranda. That to me was devotion.His hatred of my Grandma was very evident. He was of the opinion it was her fault that my mother had mental ill-health. When I stayed at East Tairei the evening mealtime was a misery. Dad “in his cups” would thump on the table expounding. (At the same time he poured great quantities of Worcestershire sauce over his dinner.) We children almost cowered from the tirade. This was practically a ritual. I could quote his remarks off by heart if necessary. It was horrible. I dreaded these sessions. To cap it all, he inferred that Grandma poisoned my mind against him. This was absolutely untrue. How thankful I was to be living in town and not in this atmosphere. All this bitterness was very distasteful to me.

*

From 1919 until his death in 1950 Nijinsky was either in mental institutions, in hospitals or an invalid. Nijinsky wrote in 1919:

From 1919 until his death in 1950 Nijinsky was either in mental institutions, in hospitals or an invalid. Nijinsky wrote in 1919:I want to weep but I cannot because my soul hurts so much that I fear for myself. I feel pain. I am sick in my soul but not in my brain. The doctor does not understand my sickness. I know what I need in order to be well. My sickness is too great for me to be cured soon. I am not incurable. I am sick in my soul. I am poor. I am a beggar. I'm unhappy. I'm hideous.

Doctors have that annoying every-recharging faith of Christians. Regardless of the catastrophic failure of Christian feeling or reason to stop evil or insanity the fountain of hope springs eternal. Our biographer of the penis says:

I can think we can do more to help someone like Nijinsky today than was possible when he became so disturbed.... Much better medication can now be prescribed for the control of disabling anxiety, fear and depression. Cyclic mood disorders can be regulated. Confusion, rage, mania, hallucinations, and disabling mental states can be managed more effectively. Interpersonal techniques, psychotherapy, and marriage counselling have become more sophisticated. "Catatonia" has almost disappeared, and the incidence of "schizophrenia" is declining. Genetic, environmental, and social sources of mental disturbance are now better understood. Special programmes for the rehabilitation of dancers and other performing artists are available in many major cities. Long-term hospitalisation of psychiatric patients is almost unheard of nowadays. (p.342)

Throughout Madness and Civilization, Foucault insists that madness is not a natural, unchanging thing, but rather depends on the society in which it exists.

Various cultural, intellectual and economic structures determine how madness is known and experienced within a given society. In this way, society constructs its experience of madness. The history of madness cannot be an account of changing attitudes to a particular disease or state of being that remains constant. Madness in the Renaissance was an experience that was integrated into the rest of the world, whereas by the nineteenth century it had become known as a moral and mental disease. In a sense, they are two very different types of madness.

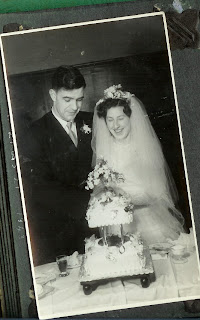

The Happy Couple

Dad was a lean wiry man and very strong. His hand grip was like a vice. The most mind-boggling thing he told us of those days was the fact that he used to carry three coils of fencing wire at a time, each weighing 50kg. One was over each arm and a third around his neck.

His descriptions of the bush written to my mother when he was courting were beautiful to read and had a clarity of expression. What impressed me most was his love of the beauty of nature. The picture he painted with words, of the rata in bloom and the bush lives in my mind still.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

Things I thought I knew

I read a lot by a guy called Foucault. He was a very interesting fellow, difficult but interesting. If you pesevere with Foucault you get some interesting ideas whereas if you persevere with someone like Derrida you end up thinking: "What the f**k?"

Ahead of his time?

"I played nervously on purpose, because the audience will understand me better if I am nervous. One must be nervous. I was nervous because God wanted to arouse the audience. The audience came to be amused. They thought I was dancing to amuse them. I danced frightening things. They were frightened of me and therefore thought that I wanted to kill them. I did not want to kill anyone. I loved everyone, but no one loved me, and therefore I became nervous. The audience did not like me, because they wanted to leave. Then I began to play cheerful things."

Here is what he actually did for his comeback:

"Suddenly the great dancer appeared, still very attractive with his muscular body, slender torso, beautifully sloping shoulders, long neck, oval face and catlike eyes. With the taut grace of a tiger he walked over to the pianist and told her to play something by Chopin or Schumann. The music started. Nijinsky picked up a chair, sat on it facing the audience, and stared back without moving a muscle. The pianist played on. Time went by. Then, the music stopped and there was dead silence. It seemed endless. The music started again. But nothing else happened. Nijinsky just sat there." (p.180)

Our biographer of the penis concludes: "Again Nijinsky was way ahead of his time."

Once Nijinsky snapped out of this he did a little jig, and then he danced "the war". "The war which you did not prevent and are also responsible for," he explained. This started off quite well but ended badly. Afterwards he showed the audience his bleeding feet. Some of the ladies he showed them to were a bit squeamish about this. He thought they wanted to have sex with him.

The Rite of Spring

On the 29th of May, 1913 Nijinsky premiered Le Sacre du Printemps.

On the 29th of May, 1913 Nijinsky premiered Le Sacre du Printemps."Sacre shows spring returning after a glacial prehistorical winter in Russia. The earth is budding with fertility, squirming with new life. There are processions and dances of people awakened. Youths and elders convene. A young virgin is chosen for the ritual sacrifice, and she dances herself to death." (p.67)

Nijinsky went in a new direction with the choreography:

"He forced the dancers to the ground, feet turned in with knees unbent, hands, elbows, and faces pointing down.... Nijinsky thrust the dancers into circles, single, double, triple, and interlocking loops of seething humanity. All conventions of classical ballet were eliminated. There was something ruthlessly primitive even bestial about his choreography." (p.67)

After a programme that began with the romantic music of Chopin setting off a classical ballet the Parisian audience were subjected to the shrieking music of Stravinsky and the anti-classical ballet of Nijinsky. There was a riot.

After a programme that began with the romantic music of Chopin setting off a classical ballet the Parisian audience were subjected to the shrieking music of Stravinsky and the anti-classical ballet of Nijinsky. There was a riot.I suppose that in 1913 Europeans thought that reason and order and pleasing music with pleasing forms was why their civilisation was great, and why war had been eliminated from the continent - a relic of a more barbaric era.

As Ignorant as Swans

Here I am on Mount Vic Lookout in May, 1998. I went to Japan the next day. The Mount Vic Lookout used to be a Maori graveyeard, but the council bulldozed it and put a viewing platform there.

Here I am on Mount Vic Lookout in May, 1998. I went to Japan the next day. The Mount Vic Lookout used to be a Maori graveyeard, but the council bulldozed it and put a viewing platform there. The Town Hall where the Joe Brown Dances used to happen every Saturday night. Imagine all that nervousness and brylcream, polished shoes and homemade frocks.

The Town Hall where the Joe Brown Dances used to happen every Saturday night. Imagine all that nervousness and brylcream, polished shoes and homemade frocks.

Uncle George

He served in the Great War. When I was about ten he took me to the local shop and bought me a pair of white gym shoes. On the way back, walking through the park, our conversation turned to Christianity; life and death anyway. How this came about I have no idea. I recall him saying: "When you die you are buried in the ground and that is the end." This statement shocked me.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

Auntie Jean (aged eleven)

In the early days at East Tairei there were no dolls to play with. Jean and the others walked up the hill behind Williamsons' store gathered tussock and made their own dolls.

Jean loved school and was eager to learn. At Outram she was dux. For two years, Standards Five and Six, the mode of travel to school was by the neighbour's horse and cart. The eldest child in that family drove the cart and was the boss. There were seats along each side and open to the elements. In wet or cold weather canvas protectors were let down and rolled up when not in use.

From a tender age Jean and Stuart were in great demand to recite at concerts. Granddad transported them in a trap all over Tairei. They were exceedingly popular and entertained often for years. They both went to elocution classes every Saturday in Dunedin. From the age of eight Jean competed in the competitions at Gore and Dunedin, gaining many certificates. In the Under 16 class in Gore, at the age of ten and eleven, she even won the Championship each year.

At the Championship in Dunedin, Jean watched the girls competing in the ballet events. When she returned home to East Tairei all the local girls lined up on the family verandah where Jean instructed them in the steps she had observed. When living in Outram Jean took ballet lessons for a short time until the teacher left.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

Auntie May

Auntie May had an ample bosom, was not very tall, had wispy slightly brownish hair, a rounded kindly face, quiet demeanour and smiling eyes.

Her frugal habits, necessary in her earlier days, were never broken. She patched and mended everything, long past the time the articles should have been relegated to the rubbish or duster bag. Sheets and knickers sported huge patches. Some members of the family felt shame at this extreme practice.

Everyone loved Auntie May. Her place was where everyone caught up on family affairs and news. Yet she was not a gossipy person. Somehow she kept her finger on the pulse of our family life. Whenever anyone wanted to find out anything about another member of our clan the answer was "Ask Auntie May".

Well into her 80's Auntie May rode her bicycle. On occasion she had a fall but this did not deter her. Finally, her family members insisted she sell her bike, for her own safety. She told me how she was sad to do this. Before parting with it she went for a short ride as a farewell gesture.

My sister Linda and I were probably the last ones to speak to her, on our Saturday afternoon visit to Ravelston Street on the 1st of October, 1983. Auntie May told us she was feeling very cold and spoke of her tiredness and diet.

Around lunchtime the next day we had a phone call from a cousin. Auntie May had died that morning sitting in her chair in the lounge. Her nieghbour had popped in before church time. There was an arrangement between them. They walked to the Musselburgh Presbyterian Church together as a rule. If one or the other was not attending they called for the collection envelope to deliver. The friend found Auntie May. The envelope was ready on the table.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

Dance - Part Four

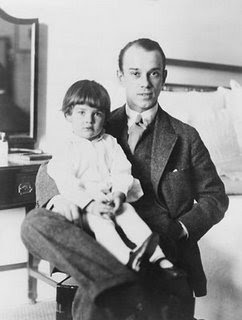

John and Maggie had four children. My father was the youngest. His closest sibling by age was Isobel. A few years ago Isobel wrote her down her memories of different family members. Her memories of her mother Maggie were slim:

John and Maggie had four children. My father was the youngest. His closest sibling by age was Isobel. A few years ago Isobel wrote her down her memories of different family members. Her memories of her mother Maggie were slim:Isobel’s memories of her father were far more detailed although not as flattering.

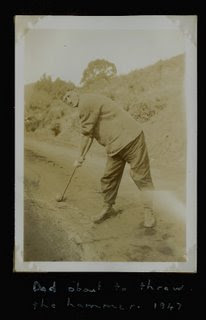

For many years I was ashamed of my father.On the rare occasions I stayed at the family home at East Tairei I dreaded the greeting from my father when he arrived home from work in the evening. As soon as he saw me his face would light up joyously. He would seize me in a crushing bear-hug, hold me close until the breath was almost squeezed out of my body, and murmur “Toby, Toby”. This was his pet name for me. Then he would kiss me full on the lips with his beery breath enveloping me. All my life I’ve abhorred the smell of beer.Dad was a hardworking and conscientious man. It was his habit to rise at 5.30a.m. to be ready to leave for work with more than ample time, to arrive at the Tairei County Council yards. When questioned about his punctuality fetish he said, “I may have a puncture to mend.” He was not an optimist.Our father had a rugged weather-beaten face and piercing intense blue eyes. His favourite flower was the carnation. In his young days he was good sportsman and was particularly adept at throwing the hammer.In bad weather he wore thigh-high gumboots for work. On arriving home he would sit in a chair and get us children to pull them off – like a tug of war. Dad played the violin by ear and kept us entertained with merry tunes. I think the violin he owned may have been his most valuable possession. His ability to amuse us with silhouettes against the kitchen wall is still remembered. Outlines of animals were preferred.Dad smoked heavily. He used a pipe and also rolled his own cigarettes. It was his practise to join two tissues together. His theory was that he did not have to stop so often to roll one.Like all men of that era he had a gold chain to wear across his waistcoat with a fob of greenstone hanging from it. He looked quite a dandy in his wedding photo. My recollections are of a man with a very wrinkly face, flushed after consuming alcohol, rather large ears, a prominent nose and calloused hands.

For many years I was ashamed of my father.On the rare occasions I stayed at the family home at East Tairei I dreaded the greeting from my father when he arrived home from work in the evening. As soon as he saw me his face would light up joyously. He would seize me in a crushing bear-hug, hold me close until the breath was almost squeezed out of my body, and murmur “Toby, Toby”. This was his pet name for me. Then he would kiss me full on the lips with his beery breath enveloping me. All my life I’ve abhorred the smell of beer.Dad was a hardworking and conscientious man. It was his habit to rise at 5.30a.m. to be ready to leave for work with more than ample time, to arrive at the Tairei County Council yards. When questioned about his punctuality fetish he said, “I may have a puncture to mend.” He was not an optimist.Our father had a rugged weather-beaten face and piercing intense blue eyes. His favourite flower was the carnation. In his young days he was good sportsman and was particularly adept at throwing the hammer.In bad weather he wore thigh-high gumboots for work. On arriving home he would sit in a chair and get us children to pull them off – like a tug of war. Dad played the violin by ear and kept us entertained with merry tunes. I think the violin he owned may have been his most valuable possession. His ability to amuse us with silhouettes against the kitchen wall is still remembered. Outlines of animals were preferred.Dad smoked heavily. He used a pipe and also rolled his own cigarettes. It was his practise to join two tissues together. His theory was that he did not have to stop so often to roll one.Like all men of that era he had a gold chain to wear across his waistcoat with a fob of greenstone hanging from it. He looked quite a dandy in his wedding photo. My recollections are of a man with a very wrinkly face, flushed after consuming alcohol, rather large ears, a prominent nose and calloused hands.My father told us many tales of his early working days up the Cairn with his father. They did fencing work. It was an area beyond Kuriwao Gorge, part of the Clinton area. They lived rough, staying out all week, often sleeping in a tent with bracken for a mattress. Wild pigs disturbed them regularly.Dad was a lean wiry man and very strong. His hand grip was like a vice. The most mind-boggling thing he told us of those days was the fact that he used to carry three coils of fencing wire at a time, each weighing 50kg. One was over each arm and a third around his neck.His descriptions of the bush written to my mother when he was courting were beautiful to read and had a clarity of expression. What impressed me most was his love of the beauty of nature. The picture he painted with words, of the rata in bloom and the bush lives in my mind still.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

Marshall approached a member of AA to enquire how we could help our father overcome his drinking problem. Mr. Fraser, father of my friend Elsie, who was a ‘dry’ alcoholic went to talk with dad. Dad agreed to try out the plan of recovery.This took a tremendous amount of willpower. My sister Rae rang me often to report progress. Dad was making a stupendous effort but the toll was devastating. He would arrive home from work, having bypassed the hotel, absolutely pouring with perspiration and trembling. This went on for some considerable time. The taunts and persuasive remarks from his workmates finally broke his resolve. He reverted to his old habits much to our disappointment.When Bun wanted to ask my father for my hand in marriage I was rather nervous. Introductions went well. Dad was affable and pleasant. Bun, in his soft voice, told Dad he wished to marry me and would Dad give his permission. Dad’s response was, “If Isobel is happy, then it’s alright with me”.

Marshall approached a member of AA to enquire how we could help our father overcome his drinking problem. Mr. Fraser, father of my friend Elsie, who was a ‘dry’ alcoholic went to talk with dad. Dad agreed to try out the plan of recovery.This took a tremendous amount of willpower. My sister Rae rang me often to report progress. Dad was making a stupendous effort but the toll was devastating. He would arrive home from work, having bypassed the hotel, absolutely pouring with perspiration and trembling. This went on for some considerable time. The taunts and persuasive remarks from his workmates finally broke his resolve. He reverted to his old habits much to our disappointment.When Bun wanted to ask my father for my hand in marriage I was rather nervous. Introductions went well. Dad was affable and pleasant. Bun, in his soft voice, told Dad he wished to marry me and would Dad give his permission. Dad’s response was, “If Isobel is happy, then it’s alright with me”.Architecture in Dunedin

Once upon a time a great deal of money used to buy a city flash architecture. Dunedin was built on the gold rushes of the 1860s. In the second half of the 19th century it was New-Zealand's premiere city.

Once upon a time a great deal of money used to buy a city flash architecture. Dunedin was built on the gold rushes of the 1860s. In the second half of the 19th century it was New-Zealand's premiere city.One man responsible for the look of Dunedin, Oamaru, and other places in the region was architect Robert Lawson. He designed First Church, Larnach Castle and Otago Boys' High School amongst other structures.

Unfortunately he came a cropper with his design of Seacliff Lunatic Asylum. Even before it has been finished there were land slips that rendered sections of the structure unsafe.

Unfortunately he came a cropper with his design of Seacliff Lunatic Asylum. Even before it has been finished there were land slips that rendered sections of the structure unsafe.After a glittering career Robert Lawson was forced to flee to Australia (how awful).

According to Michael King there were darker reasons that Seacliff was doomed:

"[Otago Maori] believed that the authorities had courted physical and psychic disaster by building the hospital over a tribal burial ground. According to this interpretation, the sturctural collapses, the fire, and the general air of terror said to prevail in the wards holding the most disturbed patients were all consequences of a failure to respect the ethos and the tapu of the location."

Dance - Part Three

His brothers are standing. One of them is going to war. He is called George. What did George believe in before he went to war?

*

"Sacre shows spring returning after a glacial pre-historical winter in Russia. The earth is budding with fertility, squirming with new life. There are processions and dances of people awakened. Youths and elders convene. A young virgin is chosen for the ritual sacrifice, and she dances herself to death." (p.67)Nijinsky went in a new direction with the choreography:"He forced the dancers to the ground, feet turned in with knees unbent, hands, elbows, and faces pointing down.... Nijinsky thrust the dancers into circles, single, double, triple, and interlocking loops of seething humanity. All conventions of classical ballet were eliminated. There was something ruthlessly primitive even bestial about his choreography." (p.67)

"Sacre shows spring returning after a glacial pre-historical winter in Russia. The earth is budding with fertility, squirming with new life. There are processions and dances of people awakened. Youths and elders convene. A young virgin is chosen for the ritual sacrifice, and she dances herself to death." (p.67)Nijinsky went in a new direction with the choreography:"He forced the dancers to the ground, feet turned in with knees unbent, hands, elbows, and faces pointing down.... Nijinsky thrust the dancers into circles, single, double, triple, and interlocking loops of seething humanity. All conventions of classical ballet were eliminated. There was something ruthlessly primitive even bestial about his choreography." (p.67)After a programme that began with the romantic music of Chopin setting off a classical ballet the Parisian audience were subjected to the shrieking music of Stravinsky and the anti-classical ballet of Nijinsky. There was a riot.

Madness! they cried from the audience.

The booing and jeering was so loud the dancers couldn't hear the orchestra. Nijinsky stood in the wings on a chair shouting numbers to his dancers while Stravinsky held on to his tuxedo tails.

Now The Rite of Spring so mainstream it has to be updated. Funny how times change. How the madness of one generation becomes the conventional in another.

Between 1913 and 1920 things didn't go too well for Nijinsky.

He had been out of the limelight for awhile by 1919 and was planning a big comeback performance. This is his version of the show:

Our biographer of the penis concludes: "Again Nijinsky was way ahead of his time."

Once Nijinsky snapped out of this he did a little jig, and then he danced "the war". "The war which you did not prevent and are also responsible for," he explained. This started off quite well but ended badly. Afterwards he showed the audience his bleeding feet. Some of the ladies he showed them to were a bit squeamish about this. He thought they wanted to have sex with him.

*

This is how George’s niece remembered him:

This is how George’s niece remembered him:George served in the Great War. When I was about ten he took me to the local shop and bought me a pair of white gym shoes. On the way back, walking through the park, our conversation turned to Christianity; life and death anyway. How this came about I have no idea. I recall him saying: "When you die you are buried in the ground and that is the end." This statement shocked me.

Fancy not believing in God after serving in WWI. Really, WWI was a PR disaster for God. All those Christians slaughtering each other for no real reason. Mind you, it took the wind out of the sails of “human reason leading us to a better world” brigade as well, the kind of people who believed in mental institutions and lobotomies.

Some years earlier than Joe Brown

A Leap Into Madness, p.57

Apparently Nijinsky's autoerotic excitement was a little bit too explicit for some tastes in the initial performance, and had to be toned down. Debussy’s music is very beautiful but it must be hard to dance to as there are no strong rhythms; the music is more of a wash of sound with a distant pulse.

Aside from the autoerotic excitement scene, Nijinsky's choreography was unusual with the dancers very much in relief. Diaghilev had taken Nijinsky to the Louvre to see Greek vases and Egyptian and Assyrian frescoes. Our friendly biographer of the penis - Ostwald - has another theory about influences on the choreography:

"Nijinsky and his sister occasionally visited the hospital where their brother Stanislav had to be confined. In 1911 he was transferred to a vey large city asylum... these visits were moving as well as troubling.... It was customary in those days to house patients with nuerological diseases together with psychiatric patients.... Pathological movements associated with these conditions can be very striking, and Nijinsky, who felt considerable empathy with his brother and had a great interest in movement, probably remembered them well." (p.58)

Balls

I went to Kapiti College. I listened to AC/DC a lot. The height of cleverness in AC/DC was a song called Big Balls. What was clever about this song was that it was talking about going to dances called balls, but - and here's where it gets clever - they were also talking about testicles.

I went to Kapiti College. I listened to AC/DC a lot. The height of cleverness in AC/DC was a song called Big Balls. What was clever about this song was that it was talking about going to dances called balls, but - and here's where it gets clever - they were also talking about testicles. I have to say my father seems to be having a much better time forty years earlier. He probably could have taught me a thing or two. I probably wouldn't have liked it if he had tried to give me advice about girls, but a few dancing tips might have relieved the boredom of an expensive night sitting around in a rented tuxedo when I was seventeen.

I have to say my father seems to be having a much better time forty years earlier. He probably could have taught me a thing or two. I probably wouldn't have liked it if he had tried to give me advice about girls, but a few dancing tips might have relieved the boredom of an expensive night sitting around in a rented tuxedo when I was seventeen.Joe Brown's Town Hall Dances

Here are the reminiscences of a (sodding) double bass player who played at Joe Brown’s dances at the Dunedin Town Hall.

Here are the reminiscences of a (sodding) double bass player who played at Joe Brown’s dances at the Dunedin Town Hall.The Town Hall was the place for Dunedin people to go to on a Saturday night. It was also the venue for visitors from out of town. No visit to Dunedin would be complete without going to Joe Brown's Town Hall Dance.

The Town Hall was used for modern dances such as foxtrots, quicksteps, jazz waltzes and Latin American dances, while the Concert Chamber was used for old time dances such as the Military Two Step, The Albert’s and Circular Waltzes.

"The dances were a marvellous sight. It was very colourful with women in their beautiful ball gowns and crowds of people watching and enjoying the dances." He believes the beginning of the end of Joe Brown's Town Hall Dances came with rock 'n' roll and pop music: "When rock 'n' roll was introduced there wasn't enough room for people to do the ballroom dances. People used to dance with each other, not at each other," he declares.

"The dances were a marvellous sight. It was very colourful with women in their beautiful ball gowns and crowds of people watching and enjoying the dances." He believes the beginning of the end of Joe Brown's Town Hall Dances came with rock 'n' roll and pop music: "When rock 'n' roll was introduced there wasn't enough room for people to do the ballroom dances. People used to dance with each other, not at each other," he declares.Mr Revill has now put away his double bass but his interest in music - particularly jazz - continues. He is a volunteer announcer with Hills AM Community Access

Do all double bass players hate pop music?