In 1998 I had just finished my M.A.

In 1998 I had just finished my M.A.I read a lot by a guy called Foucault. He was a very interesting fellow, difficult but interesting. Here is the beginning of his preface to The Order of Things:

This book first arose out of a passage in Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought - our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography - breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten our age old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes "a certain Chinese encyclopaedia" in which it is written that "animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies." In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap... is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own [system of thought], the impossibility of thinking that.

The Order of Things, Foucault, p.xv

Foucault was very big on categories, on how they appear natural to us but are actually fairly arbitrary intellectual systems that have changed radically throughout history.

His first two books were about the definition of madness and the development of the mental institution.

This book first arose out of a passage in Borges, out of the laughter that shattered, as I read the passage, all the familiar landmarks of my thought - our thought, the thought that bears the stamp of our age and our geography - breaking up all the ordered surfaces and all the planes with which we are accustomed to tame the wild profusion of existing things, and continuing long afterwards to disturb and threaten our age old distinction between the Same and the Other. This passage quotes "a certain Chinese encyclopaedia" in which it is written that "animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camel hair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies." In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap... is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own [system of thought], the impossibility of thinking that.

The Order of Things, Foucault, p.xv

Foucault was very big on categories, on how they appear natural to us but are actually fairly arbitrary intellectual systems that have changed radically throughout history.

His first two books were about the definition of madness and the development of the mental institution.

*

Some time after the birth of Marshall my mother became mentally ill. She was admitted to Seacliff Hospital. Apparently, she spent a few weeks there and was allowed home with strict instructions that she was to be taken care of. Dad’s sister, Auntie Jessie, came down from Timaru to stay with her husband Doug in tow. From all accounts Auntie Jessie was pregnant at the time and had a miscarriage so Mum ended up looking after her. Mum had a relapse and was returned to hospital and lived there for the rest of her life.

Some time after the birth of Marshall my mother became mentally ill. She was admitted to Seacliff Hospital. Apparently, she spent a few weeks there and was allowed home with strict instructions that she was to be taken care of. Dad’s sister, Auntie Jessie, came down from Timaru to stay with her husband Doug in tow. From all accounts Auntie Jessie was pregnant at the time and had a miscarriage so Mum ended up looking after her. Mum had a relapse and was returned to hospital and lived there for the rest of her life.Dad could have divorced my mother as she was a resident at Seacliff Hospital for many years, but he chose not to. I was struck by the fact that he regularly watered and cared for her asparagus fern on the front veranda. That to me was devotion.His hatred of my Grandma was very evident. He was of the opinion it was her fault that my mother had mental ill-health. When I stayed at East Tairei the evening mealtime was a misery. Dad “in his cups” would thump on the table expounding. (At the same time he poured great quantities of Worcestershire sauce over his dinner.) We children almost cowered from the tirade. This was practically a ritual. I could quote his remarks off by heart if necessary. It was horrible. I dreaded these sessions. To cap it all, he inferred that Grandma poisoned my mind against him. This was absolutely untrue. How thankful I was to be living in town and not in this atmosphere. All this bitterness was very distasteful to me.

Stories for my Grandchildren, Isobel Spence

*

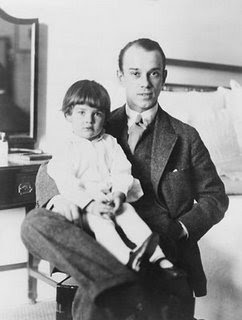

From 1919 until his death in 1950 Nijinsky was either in mental institutions, in hospitals or an invalid. Nijinsky wrote in 1919:

From 1919 until his death in 1950 Nijinsky was either in mental institutions, in hospitals or an invalid. Nijinsky wrote in 1919:I want to weep but I cannot because my soul hurts so much that I fear for myself. I feel pain. I am sick in my soul but not in my brain. The doctor does not understand my sickness. I know what I need in order to be well. My sickness is too great for me to be cured soon. I am not incurable. I am sick in my soul. I am poor. I am a beggar. I'm unhappy. I'm hideous.

Doctors have that annoying every-recharging faith of Christians. Regardless of the catastrophic failure of Christian feeling or reason to stop evil or insanity the fountain of hope springs eternal. Our biographer of the penis says:

I can think we can do more to help someone like Nijinsky today than was possible when he became so disturbed.... Much better medication can now be prescribed for the control of disabling anxiety, fear and depression. Cyclic mood disorders can be regulated. Confusion, rage, mania, hallucinations, and disabling mental states can be managed more effectively. Interpersonal techniques, psychotherapy, and marriage counselling have become more sophisticated. "Catatonia" has almost disappeared, and the incidence of "schizophrenia" is declining. Genetic, environmental, and social sources of mental disturbance are now better understood. Special programmes for the rehabilitation of dancers and other performing artists are available in many major cities. Long-term hospitalisation of psychiatric patients is almost unheard of nowadays. (p.342)

Throughout Madness and Civilization, Foucault insists that madness is not a natural, unchanging thing, but rather depends on the society in which it exists.

Various cultural, intellectual and economic structures determine how madness is known and experienced within a given society. In this way, society constructs its experience of madness. The history of madness cannot be an account of changing attitudes to a particular disease or state of being that remains constant. Madness in the Renaissance was an experience that was integrated into the rest of the world, whereas by the nineteenth century it had become known as a moral and mental disease. In a sense, they are two very different types of madness.

Ultimately, Foucault sees madness as being located in a certain cultural "space" within society; the shape of this space, and its effects on the madman, depend on society itself.His central argument [about madness and art], however, rests on the idea that modern medicine and psychiatry fail to listen to the voice of the mad, or to unreason. According to Foucault, neither medicine nor psychoanalysis offers a chance of understanding unreason. To do this, we need to look to the work of "mad" authors such as Nietzsche, Nerval and Artaud. Unreason exists below the surface of modern society, only occasionally breaking through in such works. But within works of art inspired by madness, complex processes operate. Madness is linked to creativity, but yet destroys the work of art. The work of art can reveal the presence of unreason, but yet unreason is the end of the work of art. This idea partly derives from Foucault's love of contradiction, but he feels that it reveals much about modern creativity.

No comments:

Post a Comment